Here is a preview of the articles in the 2019 Journal:

In a day and age when most natural mysteries have been solved, it is good to know that there are still some questions without answers. Mike Bryant tells of phenomena with no clear cause in his article, Distant Thunder: Ghost Artillery in the Early American West. In it, Mike collects accounts of early western travelers who noted sounds that reminded them of faraway cannon. These unexplained booming sounds fuel the imagination and defy clear explanation to this day. Sadly, Mike passed away this spring, but the Journal and staff are honored to have had the chance to work with Mike to publish this article.

Picture a mountaineer leaving rendezvous or trading post equipped to set off on a hunt with rifle propped across his saddle pommel, powder horn and shooting bag completing a picture of self-reliance. In The Cost of Shooting a Gun in the Rocky Mountain West, Michael Schaubs takes information from two mountain trading posts and uses them to estimate the cost of ammunition for mountaineers of the rendezvous period. Without lead for bullets, powder for propellent, and the flint or cap to ignite the load, a trapper’s rifle was just a ten-pound steel and wood club. In the Mountain West supplies were available to the hunters at the end of a long supply line, making these basic necessities precious. Based on Michael’s calculations, the financial cost of a missed shot was more than the embarrassment of poor marksmanship.

Six years ago, in Volume 7 of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Journal, we included an article about Murthly Castle, William Drummond Stewart’s home in Scotland. This year we add an additional piece to the international story of this Rocky Mountain character. Alan McFarland’s article, William Drummond Stewart, The H’ar of the Grizzly in Him, sets the record straight about Stewart’s service as a teenaged cavalryman in the British Army during the culminating battle of the Napoleonic Wars at Waterloo. Stewart’s military service helped finance his travels in the West, gave him credibility among the mountaineers, and may have been why he was given responsibilities in fur trade caravans, although neither trapper nor fur trader. “Captain Stewart,” as he was often called by those who mentioned him in their journals and reminiscences, has an influence on the study of the Rocky Mountain fur trade to this day. His novels based on his time in the West provide descriptions and notes useful to historians and, more importantly, it was Stewart who paid artist Alfred Jacob Miller to attend the rendezvous of 1837 and make a visual record of the trip.

Many who study the history of the Rocky Mountain fur trade can recite the places where each year’s rendezvous took place from 1825 through 1840. When the list gets to 1834 the immediate answer is, “Ham’s Fork.” 1834 was the rendezvous when the Rocky Mountain Fur Company reneged on their supply agreement with Nathaniel Wyeth, Nez Perce warrior The Bull’s Head chased a buffalo into camp as a joke, William Marshall Anderson described the happy chaos and John Townsend lay sick in his blankets enduring the noise. In Nathaniel Wyeth: Double Crossed on the Green River, Jim Hardee establishes that many of the events that the rendezvous of 1834 is noted for happened, not at Ham’s Fork, but 25 miles to the northeast at a site along the Green River.

Firearm history is a passionate area of interest that can become the focus of a lifetime of research, and within the study of the Western fur trade, can be its own specialty. Vic Barkin’s contribution to this year’s Journal, American Contracted Rifles of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade, describes the basic American-made trade rifle with a digest of known material, along with some new findings, about this important item of commerce. Vic aims his article at those students of Rocky Mountain fur trade history who have not yet made firearms a part of their studies. He hopes that some of those new to the history of this important tool of the mountaineers will have their interest piqued, giving them a whole new class of reference books to buy. Refer to the endnotes for titles.

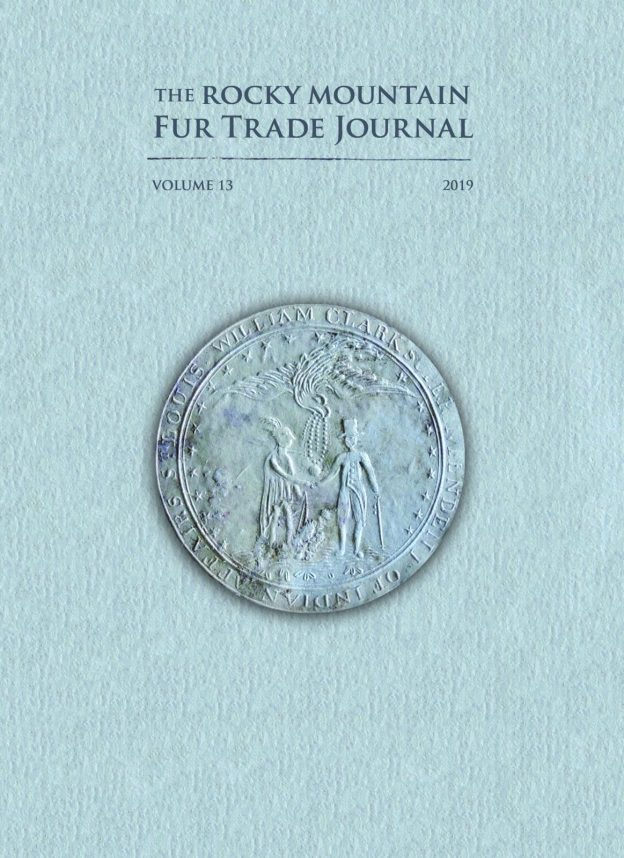

The administrative and legal aspects of the fur trade may not fit its popular image of free-wheeling adventure. The business was licensed according to Federal law, and those licenses were carried by traders as they traveled beyond the settlements to show they were in compliance with those laws. The Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Journal is trying something new this year in Licenses to Trade with Indians. Transcripts and facsimiles of documents pertaining to licensing the trade are presented to tell their own story. Our aim is to call attention to these permits, the laws that required them, and the administrative documentation of licenses issued by Superintendent of Indian Affairs, William Clark, and his agents. Included are images of two trading licenses, issued during the 1830s, which include the names of those being permitted to trade, as well as the places where legal trading was to take place under each license.