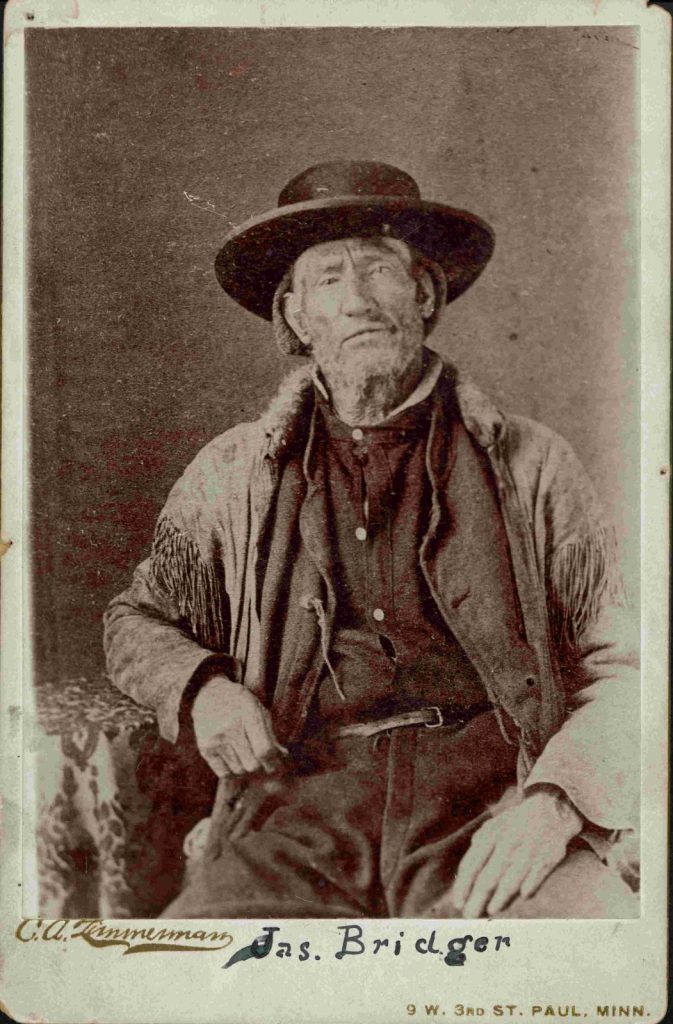

The name most associated with the rugged lifestyle of a mountain man is that of James Bridger. Born in 1804 Virginia, like many frontier families the Bridger’s moved west chasing a fresh start in the Illinois Territory, squatting near the bustling city of St. Louis, Missouri. Suffering the deaths of his parents and brother, Jim and his sister were left orphans and it fell to the thirteen-year old lad to support his sister and himself. First finding employment on a flatboat ferry, Jim later apprenticed to master gunsmith Phillip Creamer, learning the blacksmithing skills that would serve him well later in life.

Destiny called for young Jim in 1822 with a newspaper advertisement seeking 100 young men to follow William Ashley and Andrew Henry up the Missouri River to trap beaver. Although not able to read the ad himself, when informed of the details Jim must have jumped at the opportunity for income and adventure.

The keelboat journey up the Missouri proved to be long and arduous, but Jim was rewarded by the spectacle of lands and peoples that served as an introduction to a lifelong obsession with the western wilderness. Jim got his feet wet (literally) trapping beaver, learning not only trapping but also skills needed to not just survive but to thrive in a hostile and challenging new environment.

One black mark on Bridger’s legacy is the oft repeated tale of Hugh Glass’s bear attack and his abandonment by two members of his party. The identities of these men have been handed down as John Fitzgerald and, questionably, a teenaged Jim Bridger. When asked by a fellow historian why Jim never denied being involved in this incident, a potential reason is that no denial would be necessary if his peers did not believe him to be that youth.

The establishment of the Oregon Trail presented a viable business opportunity. Jim and partner Luis Vasquez located a site along the Black’s Fork River offering sizeable, well-watered grazing grounds and built a small trading post in 1843, catering to passing emigrant trains. By this point of their journey, many wagons were in need of repair and Jim provided this service by adding a blacksmith shop, capitalizing on his skills learned as a youth.

After the last rendezvous in 1840, the nature of the fur trade in the Rocky Mountains underwent major upheaval. Beaver trapping no longer held the financial inducement it once had, forcing trappers to look for alternate means of support. Many left the mountains returning to homes in the east or traveling west to settle in Oregon or California. Jim, his heart in the Rocky Mountains, looked for a way to remain in his mountain lifestyle.

The establishment of the Oregon Trail presented a viable business opportunity. Jim and partner Luis Vasquez located a site along the Black’s Fork River offering sizeable, well-watered grazing grounds and built a small trading post in 1843, catering to passing emigrant trains. By this point of their journey, many wagons were in need of repair and Jim provided this service by adding a blacksmith shop, capitalizing on his skills learned as a youth.

Jim was said to possess a virtually photographic memory for terrain and landmarks, proving to be much in demand as a guide in following years. He piloted many notable expeditions including the US Army Topographic Engineers under Captain Howard Stansbury, laying out a potential route for the transcontinental railway. What came to be known as Bridger Pass and the Overland Trail eventually led to the Interstate 80 corridor across today’s Wyoming. Jim also guided topographers and geologists such as the Lieutenant G. K. Warren scientific expedition in 1856, and government sponsored mapmakers Ferdinand Hayden and William Raynolds bound for the headwaters of the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers in 1859-60. The US military sought Bridger’s lead on several campaigns, including the 1857 Utah Expedition and the Powder River Campaign of 1865.

Age finally caught up with Jim, and after he was turned down for the office of Indian Agent for the Crow tribe, he spent the last thirteen years of his life on his farm near Westport, Missouri, living quietly with his two daughters and their families. Bridger died in 1881.

In many ways, Jim Bridger’s life paralleled a young westering America, from humble origins, striving to overcome challenges by dint of hard work and restless pursuit of a dream. Jim proved to be a self-made man and helped lead the way for manifest destiny. He should be remembered as an American icon and the standard by which his contemporaries are judged. He left a legacy far beyond beaver.

RECOMMENDED READING

Jerry Enzler, Jim Bridger, Trailblazer of the American West (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2021). Buy now.

J. Cecil Alter, Jim Bridger, A Historical Narrative (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950, 2nd Edition 1962). Buy now.