By Museum of the Mountain Man Staff

Two hundred years after the height of the Rocky Mountain fur trade, beaver are still busy along the tributaries of the Snake, the Missouri, and the upper Green River and countless other streams that once held these fur bearing mammals. They go about their work mostly uninterrupted, much as they always have. The same cannot be said of the mountain men who once set their traps along these waters. Today, they exist chiefly in journals, memoirs, and the footnotes of historians.

Would early nineteenth-century trappers have been surprised to learn that beaver would recover, even as the profession built upon their pursuit vanished? During the early Rocky Mountain fur trade, beaver in western rivers were routinely described as “plentiful” and “abundant.”[1] Yet even as the fur trade expanded, trappers, keen observers of the landscape, recognized that familiar streams could be “trapped out,” that pelts grew harder to come by, and that profits declined where competition was heavy.[2] Whether their concern was practical or philosophical, it was real. Time has shown that while beaver populations recovered, the occupation built on their pursuit did not.

Abundant Beaver in Streams

In the early 1800s, beaver populations in rivers and streams west of the Mississippi appeared inexhaustible. Trapper Joseph Meek noted that the “beaver were very plenty on Henry’s fork” in 1830.[3] The following year, mountain man Warren Ferris described the Snake River and Henry’s Fork in glowing terms, noting that his party was able to take “from forty to seventy beaver a day,” a reflection of the optimism that characterized the early Rocky Mountain fur trade.[4] For trappers, each drainage promised a new opportunity, each river a potential bonanza. If one stream failed to meet expectations, another lay in the next drainage ahead, promising abundant fur.

This confidence was not mere fantasy. William Ashley noted in his 1825 journal information that Jedediah Smith learned from Peter Skene Ogden during his time at Flathead Post:

Mr. Smith ascertained from the gentleman who had charge of that establishment, that the Hudson Bay Company had then in their employment, trading with the Indians and trapping Beaver on both sides of the Rocky Mountains, there were about 80 men, 60 of whom were generally employed as trappers and confined their operations to that district called the Snake country, which Mr Smith understood as being confined to the district claimed by the Shoshone Indians. It appeared from the account, that they had taken in the last four years within that district eighty thousand Beaver, equal to one hundred and sixty thousand pounds of furs.

You can form some idea of the quantity of Beaver that country once possessed when I tell you that some of our hunters had taken upwards of one hundred in the last spring hunt out of streams which had been trapped, as I am informed, every season for the last four years.[5]

Early trapping parties encountered astonishing numbers of beaver, before experience and growing competition revealed the limits of even the richest streams.

Growing Awareness of Scarcity

Even as optimism prevailed, trappers’ journals reveal a growing awareness that local depletion was real. Jedediah Smith, in his 1830 letter to the Secretary of War and referring to Hudson’s Bay Company brigades, observed that “the territory … being trapped by both parties, is nearly exhausted of beavers, and unless the British can be stopped, will soon be entirely exhausted.”[6] (Read here: Jed’s Famous 1830 Letter – The Jedediah Smith Society)

Streams that once yielded abundant pelts had become increasingly labor-intensive. Trappers also noted a decline not only in the number of animals but in their size. In 1832, Robert Campbell wrote:

When we trapped the first time in the country, they would average more. It would not take 60 beavers to made a hundred pounds, as the old beavers, before they were trapped out, weighed more than young beavers.[7]

By the early 1830s, similar observations appeared with increasing frequency. Nathaniel Wyeth remarked in 1832 that the beaver “had lately been trapped out.”[8] In 1835, Osborne Russell recorded reports from Shoshone people he encountered in the Lamar Valley indicating that beaver were “comparatively scarce” in the greater Yellowstone Lake region.[9] Robert Newell, a mountain man working in the Powder River area, noted in 1838 that “times is getting hard all over this part of the Country beever Scarce and low all peltries are on the decline.”[10] By 1839, Russell reported that “Beaver also were getting very scarce” in the Bear River area.[11]

Osborne Russell further recalled:

The trappers often remarked to each other as they rode over these lonely plains that it was time for the White man to leave the mountains as Beaver and game had nearly disappeared.[12]

This recognition extended beyond the trappers themselves. In 1839, Dr. Friedrich Adolph Wislizenus, a German physician, botanist, and explorer, traveled west with a supply caravan to the Green River rendezvous. While documenting the regions botanical landscape, he also observed the business of the Rocky Mountain fur trade. He wrote:

The beaver formerly spread over the greater part of the United States. From the cultivated portions he has disappeared long ago; and in his present home, in the Rocky Mountains, he is beginning to become scarcer. Hundreds of thousands of them have been trapped there in the last decades, and a war of extermination has been waged against the race. The consequence is that they are now found only singly in regions that were formerly well known for their abundance of beavers. It is only in the lands of hostile Indians, the Blackfeet, for instance, that they still exist in greater numbers, because the Indians do not specially occupy themselves with beaver trapping.[13]

This awareness was practical rather than sentimental. Concern over declining beaver numbers was likely driven less by environmental alarm than by the loss of income, but mountain men clearly recognized the changes taking place in the streams. Descriptions of beaver populations shifted from “abounding” and “plentiful” to “scarce” and finally to “trapped out.” They noticed patterns of scarcity, differences between river systems, and the consequences of repeated trapping. In short, they were early experts in local population dynamics—even if they lacked the vocabulary of modern ecology.

Trapped Out, by Design

Declining numbers were not just an individual concern, they were also the result of corporate strategy. Beaver was a competitive resource and trapping out regions, or deliberately creating “fur deserts,” was intended to deny resources to rivals.[14]

Hudson’s Bay Company Governor George Simpson openly encouraged depletion of beaver in certain regions to deny Americans access. During an 1824 visit to the Columbia District, he wrote:

If properly managed no question exists that [the Snake County] would yield handsome profits as we have convincing proof that the country is a rich preserve of Beaver and which for political reasons we should endeavor to destroy as fast as possible.[15]

Wislizenus also noted the long-term consequence of this policy and what he described as “ruthless trapping”:

The Hudson’s Bay Company has established more system in beaver trapping within its territories. It allows trapping only at certain seasons, and when beavers get scarce in any neighborhood, trapping is strictly forbidden there for some years. In regions, however, on whose permanent possession the company does not count, it allows the trappers to do as they please. But if trapping is carried on in this ruthless fashion, in fifty years all the beavers there will have disappeared, as have those in the east, and the country will thereby lose a productive branch of commerce.[16]

Joe Meek noted the 1838 rendezvous was held at “Bonneville’s old fort on Green River, and was the last one held in the mountains by the American Fur Company. Beaver were growing scarce, and competition was strong.”[17] Later that year Meek and his companions “visited the old trapping grounds on Pierre’s Fork, Lewis’ Lake, Jackson’s River, Jackson’s Hole, Lewis River and Salt River: but beaver were scarce.”[18]

For the independent or company-employed trapper, declining numbers meant economic hardship. For company managers, depletion was a calculated tool. In either case, trappers were aware that beaver were a finite resource.

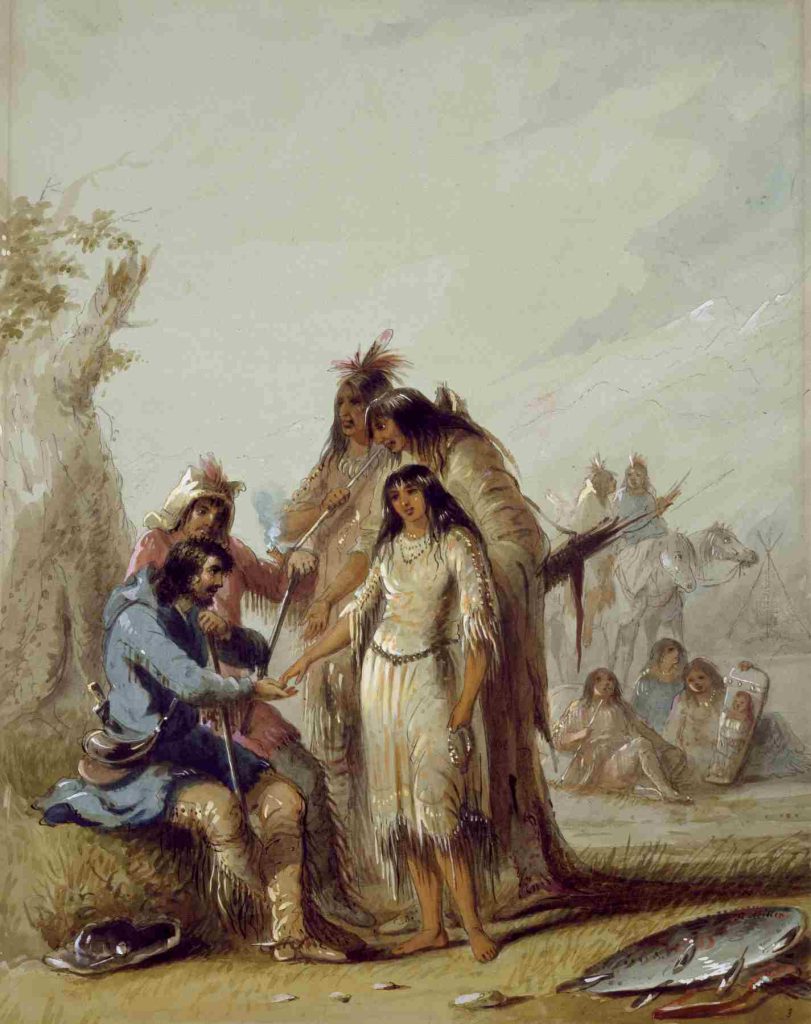

The Vanishing Mountain Man

The experiences of individual trappers reflect this broader shift. In his memoirs, Kit Carson recalled that by 1841, the changing landscape of the fur trade had forced many men to abandon trapping altogether:

Beaver was getting scarce, and, finding it was necessary to try our hand at something else, Bill Williams, Bill New, Mitchell, Frederick, a Frenchman, and myself concluded to start for Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas. [19]

There, Carson was hired to hunt for the fort. [20]

Mountain men became legendary almost as soon as the fur trade took shape in the Rocky Mountains. Yet their presence in the mountains proved fleeting when measured against the persistence of the beaver they pursued. By the 1830s and 1840s, changing fashions, markets, and economic conditions diminished demand for beaver hats and the need for long-term trapping expeditions. Though the beaver endured, the profession that relied on them did not.

The Resilient Beaver

Two hundred years later, the irony is unmistakable. Rivers once feared stripped bare of beaver continue to support thriving populations.

In the long contest between trapper and his prey, the beaver proved the more durable. Trappers correctly warned of local scarcity, but few foresaw how briefly their own profession would last. The rivers remain, the beaver endure, yet the mountain men are gone. Their words, however live on, offering a quiet irony and a reminder that the beaver is the unexpected victor of the story of the Rocky Mountain fur trade.

The Rocky Mountain fur trade may be history, but beaver continue to offer a surprise. Learn more:

How Beavers Are Restoring Wetlands in North American Deserts!

[1] For examples of journal entries remarking on an abundance of fur bearers, see: Peter Skene Ogden, “Journal of Peter Skene Ogden; Snake Expedition, 1828–1829,” Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society 11, no. 4 (December 1910): 394; Warren Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, eds. Paul C. Phillips and Fred A. Rosenstock (Denver, CO: The Old West Publishing Company, 1942), 97; Frances Fuller Victor, The River of the West (Columbus, OH: Long’s College Book Co., 1952; reprint of original edition), 94.

[2] Robert Campbell, A Narrative of Colonel Robert Campbell’s Experiences in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade, 1825–1835, ed. Drew Alan Holloway (Fairfield, WA: Ye Galleon Press, 1976), 42.

[3] Victor, River of the West, 64.

[4] Ferris, Life in the Rocky Mountains, 97.

[5] Dale Morgan, ed., The West of William H. Ashley, 1822–1838, ed. Dale Morgan (Denver, CO: The Old West Publishing Company, 1964), 118, 288n211.

[6] Dale L. Morgan, Jedediah Smith and the Opening of the West (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1953), 343–348.

[7] Campbell, Narrative, 42.

[8] Jim Hardee, Obstinate Hope: The Western Expeditions of Nathaniel J. Wyeth, Volume One, 1832–1833 (Pinedale, WY: Sublette County Historical Society/Museum of the Mountain Man, 2013), 141.

[9] Osborne Russell, Journal of a Trapper, ed. Aubrey L. Haines (Portland, OR: Champoeg Press, Reed College, for the Oregon Historical Society, 1955), 27.

[10] Robert Newell, Robert Newell’s Memoranda: Travels in the Territory of Missouri; Travel to the Cayuse War; Together with a Report on the Indians South of the Columbia River, ed. Dorothy O. Johansen (Portland, OR: Champoeg Press, 1959), 36.

[11] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 112.

[12] Russell, Journal of a Trapper, 123.

[13] F. A. Wislizenus, A Journey to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1839 (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1912), 121.

[14] Jennifer Ott, “‘Ruining’ the Rivers in the Snake Country: The Hudson’s Bay Company’s Fur Desert Policy,” Oregon Historical Quarterly 104, no. 2 (Summer 2003):166-195.

[15] George Simpson, Fur Trade and Empire: George Simpson’s Journal: “Remarks Connected with the Fur Trade in the Course of a Voyage from York Factory to Fort George and Back to York Factory, 1824–1825,” ed. Frederick Merk (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1931), 46.

[16] F. A. Wislizenus, A Journey to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1839 (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1912), 122. Wislizenus, Journey to the Rocky Mountains, 122.

[17] Victor, River of the West, 255.

[18] Victor, River of the West, 263.

[19] Harvey Lewis Carter, Dear Old Kit: The Historical Christopher Carson (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968), 79.

[20] Carter, Dear Old Kit, 79.