By Museum of the Mountain Man Staff

February often invites reflection on love and relationships, but courtship in the Rocky Mountain fur trade looked very different from the sentimental ideals of formal dances and letters familiar to many Americans in the early nineteenth century. Yet, trapper Jim Beckwourth observed, “Even the untutored daughters of the wild woods need a little time to prepare for such an important event, but long and tedious courtships are unknown among them.”1

Winter Camps and the Conditions for Courtship

Winter months offered more opportunities for social interaction. With travel limited, people gathered in camps and posts, where storytelling, music, shared work, and conversation created conditions for relationships to develop. Men working for operations such as the American Fur Company, Hudson’s Bay Company, and Rocky Mountain Fur Company often spent years away from eastern homes. In this environment, bonds developed within winter camps, trading posts, and Indigenous communities rather than through the formal courtship rituals common in Euro-American society.

Courtship, Ceremony, and Exchange

Courtship in the wilderness followed familiar emotional patterns, even as it adapted to frontier realities. Contemporary author Washington Irving described the effects of winter’s isolation along the Salmon River in 1832:

Idleness and ease, it is said, lead to love, and love to matrimony, in civilized life, and the same process takes place in the wilderness … one of the free trappers began to repine at the solitude of his lodge, and to experience the force of that great law of nature, “it is not meet for man to live alone.”2

Seeking companionship, that lonely trapper turned to a Nez Perce leader, with a request shaped by the realities of frontier life:

I want … a wife. Give me one from among your tribe. Not a young, giddy-pated girl, that will think of nothing but flaunting and finery, but a sober, discreet, hard-working squaw; one that will share my lot without flinching … that can take care of my lodge, and be a companion and a helpmate to me in the wilderness.3

After two days of consultation, the leader returned with a bride, accompanied by her extended family.

The trapper received his new and numerous family connection with proper solemnity … After several pipes had been filled and emptied in this solemn ceremonial, the chief addressed the bride; detailing, at considerable length, the duties of a wife; which, among Indians, are little less onerous than those of the pack-horse; this done, he turned to her friends, and congratulated them upon the great alliance she had made. They showed a due sense of their good fortune, especially when the nuptial presents came to be distributed among the chiefs and relatives, amounting to about one hundred and eighty dollars.4

Within only a few days, the trapper had his bride, illustrating how ceremonial exchange established both marital and social bonds within fur trade society. Marriage and courtship in the fur trade were seldom private arrangements between two individuals. They rarely involved written love letters or formal proposals. Instead, it was often a public act involving kinship networks and reciprocal obligations, guided by cultural norms sometimes referred to as the “custom of the country.”5 Another onlooker explained:

If the parties are mutually agreeable to each other, there is a consultation of the family, if this is also favorable, the father of the girl, or whosoever giver her in marriage, makes a return for the present he had previously received from the lover — the match is then concluded.6

Contemporary observers described these marriage customs as grounded in family consultation and exchange, as opposed to the “horrors of such prolonged purgatory” common in traditional Euro-American courting.7

While these marriages often appeared informal to outsiders, they were socially regulated and mutually beneficial. Traders gained access to crucial survival skills, including food preparation, hide processing, clothing production, and geographic knowledge. Indigenous families benefitted from these unions by gaining stronger trade relationships and better access to valuable goods. While some marriages were temporary, many endured for decades and produced families whose descendants helped shape western communities.

Love, Loss, and Separation

Contrary to a common misconception, not all fur trade marriages ended quickly. While some traders returned east and abandoned their country marriages, leaving women and children behind, others returned east with their Native families or remarried under church law.8 Some remained in the West, becoming among the earliest settlers during the settlement period.9

Undoubtedly many of these unions were temporary leading one chronicler to describe them as “connections [that] frequently take place for a season … but are apt to be broken when the free trapper starts off … on some distant and rough expedition.10

However, time and distance sometimes did make the heart grow fonder, as demonstrated in a dramatic episode, also recorded by Washington Irving, in which two trappers sought to renew relationships with Native women—one of whom had married since their last meeting. An attempted elopement led to pursuit, confrontation, and ultimately negotiation. Violence was narrowly avoided, and the aggrieved husband accepted compensation—two horses—for his loss, remarking that they were “very good pay for one bad wife.”11 Click to read full account

One could argue that the episode ended with negotiation rather than romance—but with Valentine’s Day approaching, it is tempting to imagine a measure of sentiment in the escapade. While fur trade relationships were inseparable from negotiation, survival, and cultural norms, they may also have been guided, at least in part, by genuine affection.

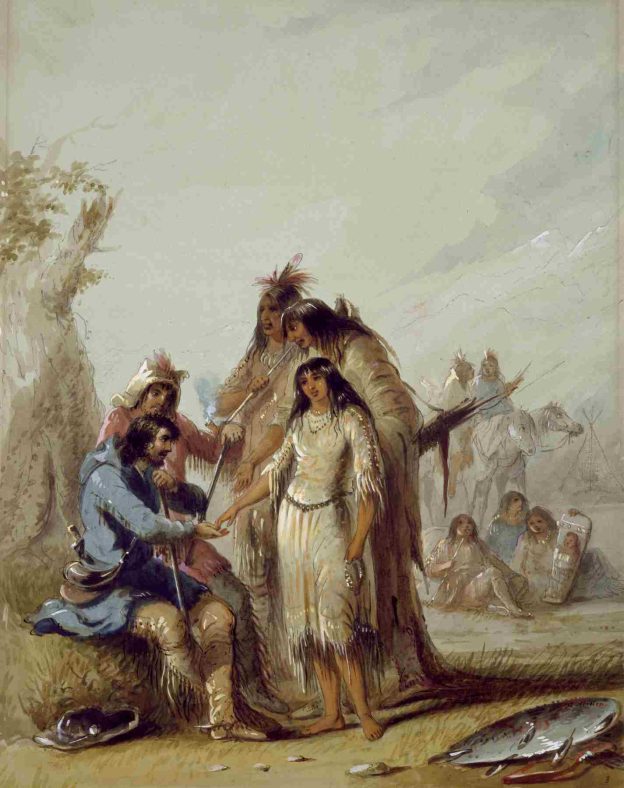

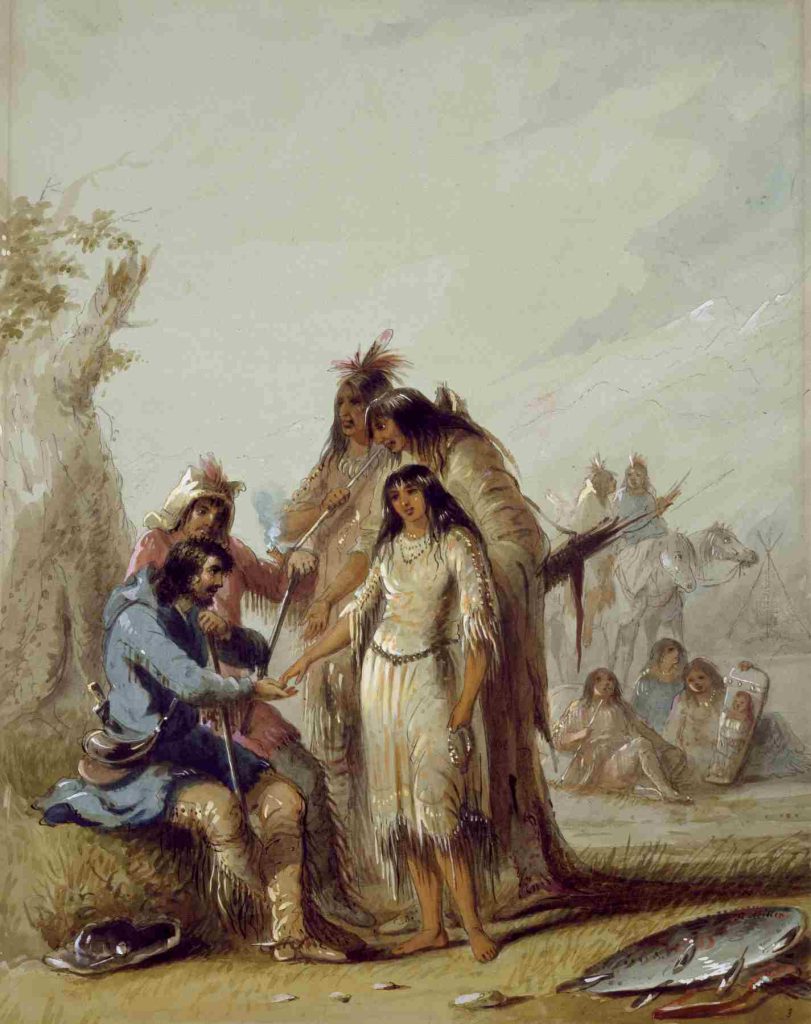

However, artist Alfred Jacob Miller, in the notes for his painting The Trapper’s Bride, reflects a somewhat jaded view:

A Free Trapper (white or half-breed), being ton or upper circle, is a most desirable match, but it is conceded that he is a ruined man after such an investment, the lady running into unheard of extravagancies. She wants a dress, horse, gorgeous saddle, trappings, and the deuce knows what beside. For this the poor devil trapper sells himself, body and soul, to the Fur Company for a number of years.12

Love on the Frontier

As we reflect on love during February, the fur trade offers a reminder that relationships have always been shaped by place, culture, and necessity, and that love on the frontier could be as complex and enduring as anywhere else. Marriage in the Rocky Mountain fur trade was neither uniformly exploitative nor purely sentimental; it was an institution shaped by mobility, mortality, cultural expectations, and economic need. Understanding these frontier relationships reveals how emotional and practical bonds, family networks, and survival were woven into the daily life of the fur trade and its enduring legacy in the Rocky Mountain West.

- James P. Beckwourth, The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, as told to Thomas D. Bonner (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1981), 148. ↩︎

- Washington Irving, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, U.S.A., in the Rocky Mountains and the Far West, Edgeley W. Todd, ed. (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961), 112. ↩︎

- Irving, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, 112. The period term “squaw,” now recognized as offensive, is quoted for historical context. ↩︎

- Irving, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, 113. ↩︎

- The term “custom of the country” seems to be an English translation of a term used in the French fur trade, a la mode du pays. Kathleen Barlow, “Trappers’ Brides: Intercultural Marriages in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade,” The Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Journal 7 (2013), 94n5. ↩︎

- Henry Marie Brackenridge, Journal of a Voyage up the Missouri in 1811 (Chicago, IL: The Lakeside Press, R. R. Donnelley & Sons, 1904), 121. ↩︎

- George Frederick Ruxton, Life in the Far West, LeRoy R. Hafen, ed. (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1951), 47. ↩︎

- Mildred Walker Schemm, “The Major’s Lady: Natawista,” The Montana Magazine of History 2, no. 1 (1952): 4–15. ↩︎

- See J. Cecil Alter, Jim Bridger (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1925); Stanley Vestal, Joe Meek: The Merry Mountain Man (Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers, 1952); Robert Newell, Memoirs of Robert Newell, Trapper and Indian Trader, Dorothy O. Johansen, ed. (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1983). ↩︎

- Irving, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, 356-359. ↩︎

- Irving, The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, 356-357. ↩︎

- Marvin C. Ross, The West of Alfred Jacob Miller (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1968), 12. ↩︎