When many think of the animals that would have graced the western landscape during the Rocky Mountain fur trade era (1820-1840), they may assume that the animals encountered by trappers and traders in Wyoming were pretty much the same as we have today. However not all iconic “western” animals were present during the time of the mountain man.

That leads to the question: Were there moose in and around the area that would become the state of Wyoming?

Surprisingly, moose were not as common as they are today in the American West, especially Wyoming. While moose in the 21st century are some of the most favorite and popular of the western animals, their presence in Wyoming has not been found in the historical accounts and narratives from the early to mid- 1800s. Many of the fur trader’s journals or letters made references to the ecology of the Wyoming mountains, but none of them mentioned seeing moose.

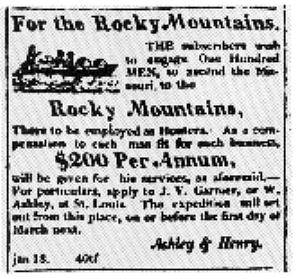

Furthermore, artist Alfred Jacob Miller (AJM), known for his portrayal of common every day scenes of the fur trade, painted multiple interactions between the mountain men and the animals of the region in 1838. Of those include hunting buffalo, bears, elk, antelope, deer, and of course beaver. However AJM never sketched or painted a moose. In addition to this lack of visual reference, further evidence that AJM and his employer William Drummond Stewart were unfamiliar with moose in the Wyoming area, can be found in what Stewart himself called his “fictitious Auto-biography” entitled Edward Warren, where he penned that “Every animal of the land, except the moose, ranged around our course, less wild because less harassed than elsewhere.” Stewart wrote this passage when his party was “…rounding the south eastern shoulder of the Mountains of the Winds.” (The Wind River Mountains are located in Wyoming.)

Earlier in Stewarts book he stated that when heading to the 1833 Rendezvous on the Green River in Wyoming that “this was almost the finest part of the west for every species of animal the country affords, excepting the moose deer, which is to be found no lower down than the hunting grounds of the Blackfeet and the Assimboines, on the far sources of the Missouri.”

Although a fictitious work, Edward Warren no doubt described in detail many of the things William Drummond Stewart saw on his trip to and through the American West. For him to make mention that the moose was an exception to the animals found in Wyoming is as thought-provoking as it is noteworthy.

One instance of moose during the fur trade was recorded by Warren Ferris in his journal when traveling by Clark’s fork river near Deer Lodge, Montana in the early 1830’s. His entry states:

“On the fourth we passed into the Deer‑house plains, and saw the trail, and several encampments, of the Rocky Mountain Fur Co.; but no game, save one antelope.

On the fifth, we passed twenty five mile, west of north, down this valley. In the mean time, our hunters killed three grizly bears, several goats, deer, and two buffaloes; the latter, however, is seldom found in this country; though it abounds in black and white tailed deer, elk, sheep, antelopes, and sometimes moose, and White mountain goats have been killed here.”

“Sometimes moose” They were indeed scarce at the time, even when sighted.

Another reference to moose during the fur trade was noted by Alexander Ross. In late October – early November, 1824, Alexander Ross and company crossed the continental divide via Lemhi Pass. Interestingly, this pass essentially crosses the Bitterroots from Montana into Idaho. Lewis and Clark crossed it on Aug. 12, 1805. Their journal indicates the pass is about 3 – 4 days travel from the Dillon, MT area. After spending much time and ammunition shooting at geese and ducks, Ross reports, “We were at the same time surrounded on all sides by herds of buffalo, deer, moose and elk, as well as grouse, pheasant, and rabbit.”

In the book The History of Wildlife Management in Wyoming published in 1987, it states that:

“Moose and mountain goat were added to the list of protected species in 1882. Section 1 of the game code read: ‘It shall be unlawful to pursue, hunt or kill any deer, elk, moose, mountain sheep, mountain goat, antelope or buffalo save only from August 1 to November 15 inclusive in each year, or kill or capture by means of any pit, pitfall or trap any of the above named animals.’ Moose were evidently extremely scarce in the area Wyoming now encompasses. Osborn Russell was a good observer and made an attempt to describe every species of big game and large predators that he observed. Russell spent a lot of time between 1834 and 1843 in the area where moose are now found in abundance but he did not mention them in his journals.”

The number of moose must have grown, although not by much, in Wyoming between the time of the fur trade and 1882 to be put on the list of animals hunted.

The History of Wildlife Management in Wyoming goes on to say that “It is also possible that some of the early explorers saw moose but called them elk after the European fashion.”

We know that Alfred Jacob Miller did not follow this fashion as his multiple paintings depicting an Elk hunt were indeed actual elk. Below is an example of this as well as an image of a moose to show that they are in fact two different animals. (Sorry Europe)

Today, moose are prominent in Wyoming. An animal that surely the mountain men would have enjoyed at the time.